Agnieszka PILAT

Thinking Machines: Renaissance 2.0

September 23 - October 31, 2021 at Modernism West

Reception for the artist Thursday, September 23, 6-8pm at Foreign Cinema

Summary

When Agnieszka Pilat first met Spot, she was astonished by the robotic dog’s ability to climb a staircase with lifelike agility. As a painter with a deep interest in innovation, Pilat was reminded of one of the 20th century’s most innovative paintings, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), by Marcel Duchamp. In his 1912 canvas, Duchamp depicted the movement of a nude woman as a series of superimposed frames, much as a machine might perceive and analyze human motion. As an artist-in-residence at Boston Dynamics – the manufacturer of Spot – Pilat was inspired to portray the innovative bio-inspired machine as Duchamp might have done.

Over the past decade, Pilat has deployed her classical training to work at the intersection of technological progress and artisanal tradition. The twelve canvases featured in her first exhibition at Modernism Gallery are meticulously executed in oil on linen, taking inspiration from Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, as well as Marcel Duchamp. But her art is no mere copy of the masters. She has not only replaced their human subjects with robots, but also ingeniously portrayed these new entities in a gestural language evocative of robotics.

“I’m interested in questions of authorship,” she says. “Authorship has traditionally been associated with the hand of the artist. What happens to authorship in a time when machines are capable of endless repetition?”

To explore these issues, Pilat has sought to embody the cutting-edge technology she witnessed at Boston Dynamics by making multiple copies of the same image. For instance, she has painted her version of Nude Descending a Staircase twice. The paintings are in different color palettes, both evocative of the Pop art of Andy Warhol, who famously said “I’d like to be a machine”. However, the difference in colors is only the most obvious contrast evident in her two paintings. Unlike Warhol, who used mechanical techniques such as silkscreening in his best-known pieces, Pilat has worked by hand, resulting in expressive discrepancies in every detail. Her efforts to paint like a robot paradoxically betray her humanity.

For Pilat, this does not amount to triumph or defeat. As she observes, “Machines are humanity’s children.” In this familial relationship, neither is inherently superior – let alone an existential threat to the other – though she acknowledges that “machines are today’s celebrities, perhaps even the aristocracy of the 21st century”. By painting their portraits, she carries on a tradition stretching from Renaissance studios to Warhol’s Factory of the 1960s.

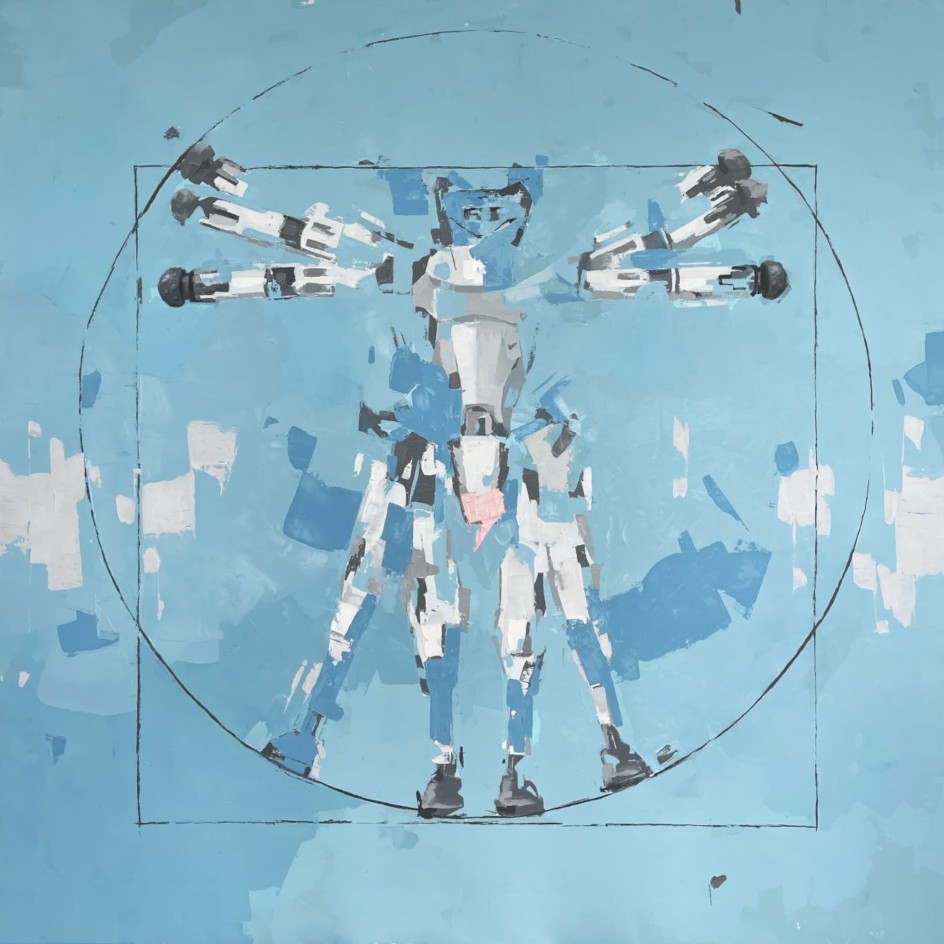

The majority of work in her Modernism exhibition focuses on the Renaissance, with images derived from Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco. Pilat sees an important connection between the Renaissance and the present moment, especially evident to her as an artist based in Silicon Valley. “Much as innovation changed the world during the Renaissance, innovators in the Bay Area and the Boston region are changing the world today,” she says. In tribute to this history, and referencing the language of software iteration, she has dubbed her new series Renaissance 2.0.

The legacy of Leonardo is especially important for Pilat, because he is generally credited with the invention of the humanoid robot. Based on records including notebook sketches, historians have shown that Leonardo designed an automaton in the form of a Germanic knight in 1495. Whether the knight was actually built at the time remains a subject of academic debate, but modern versions have shown that his automaton worked. And the mechanical principles, which would be familiar to any present-day roboticist, were partially derived from his studies of human proportions inspired by the ancient Roman texts of the architect/engineer Vitruvius.

In her version of Vitruvian Man, Pilat has aptly replaced the human figure with a humanoid robot. First designed by Boston Dynamics in 2013, and named after the most famous of pre-Olympian gods, Atlas is a direct mechanical descendent of Leonardo’s humanoid and the living knights it emulated. The robot also represents a new ideal, engineered by analyzing the physics of human motion. Pilat’s paintings provocatively show this new ideal in a classical visual language familiar to everyone.

Even more provocative is Pilat’s reinterpretation of Michelangelo. Her paintings are based on the most famous section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling where Michelangelo depicts God giving life to Adam. She includes only the portion where their fingers touch, substituting robotic arms for their musculature.

The robotic arm was one of the first fixtures of modern robotics. For all that they’ve changed over the decades that they’ve extended their reach from the factory floor to the surgical theater, the morphology has remained remarkably consistent. Much as God is said to have created man in His image – and all people today are said to be descendants of Adam – technology has a long lineage that can be construed as a self-perpetuating phenomenon.

Pilat captures the genesis of today’s most sophisticated machinery in a Biblical vernacular. Machines may be humanity’s children, but she suggests that (like the humans begat by God) they also have lives of their own. In the venerable tradition of Marcel Duchamp, Pilat is a conceptual artist as much as she’s a painter. Her Sistine Chapel paintings are philosophical essays on the nature of technology that simultaneously reconsider the agency of the artist in the machine age.

In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936), the cultural critic Walter Benjamin famously observed, “the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.” By doing the work of a machine by hand, Pilat seeks to renew the aura of uniqueness in each copy she creates.

Pilat also moves her paintings into the conceptual realm through a literal amalgamation of oil paint with the latest digital imaging techniques. By holding a smartphone up to paintings such as Sistine Chapel and Nude Descending a Staircase, viewers can see the robots that inspired them, and can watch the robots in motion. Evocative of Duchamp’s use of transparency in his Large Glass, this augmented-reality layer reconnects her paintings with his conceptual aspirations to advance human perception by carrying Cubism into the fourth dimension.

Agnieszka Pilat is a painter of the modern condition. Conditioned by the latest technology, her paintings evoke a future in which the relationship between humans and machines is as fluid as augmented reality.